I spend a lot of my time thinking about what the Bible says and what the Church does with what the Bible says. How you and I involve the Bible in justifying our actions or those of others should be held up to rigorous scrutiny.

The importance of this simple observation is evident in the current debate over Franklin Graham’s support of President Trump’s executive order temporarily banning refugees and immigrants from several countries. In an article on the HuffPost website, Graham used the phrase, ‘That’s not a Bible issue’ and it is this wording (and what it implies) that I’d like to explore. I’m not claiming this to be an analysis of the whole debate, or that I am able to offer an authoritative voice on all the issues. I do, however, want to attempt to bring some clarity to this one particular aspect of how the Bible has been used.

To begin with let’s quote the relevant passage in the HuffPost article (posted 25.1.2017):

The Huffington Post spoke with Graham on Wednesday, and asked whether it’s possible to reconcile Trump’s temporary ban on refugees with the Christian commandment to welcome, clothe and feed the stranger, and to be a Good Samaritan to those in need.

Graham said he doesn’t believe those two things need to be reconciled.

“It’s not a biblical command for the country to let everyone in who wants to come, that’s not a Bible issue,” Graham told HuffPost. “We want to love people, we want to be kind to people, we want to be considerate, but we have a country and a country should have order and there are laws that relate to immigration and I think we should follow those laws. Because of the dangers we see today in this world, we need to be very careful.”

A former colleague of mine here at Redcliffe used to give students three questions to ask when reading something, to which I have added my own annotations. There are many other questions we could ask, of course, but let’s stick with these three.

‘What are you saying?’ This is a question of clarity. Have I taken the time to be clear on what the author/speaker is (and is not) actually claiming? This matters in terms of accuracy but is also a matter of principle and respect to the person writing/speaking.

‘How do you know?’ This is a question of methodology. How has the author arrived at their claim? What assumptions have they made to get there? What logical steps have led them to this conclusion?

‘So what?’ This is a question of significance. What are the implications of what the speaker has said? This could be significance in terms of what it reflects about the author’s context and role (especially when in a position of influence). It also has to do with the practical consequences of what they are saying, or the effect their words may have beyond their own immediate action. We might say, if people take this word seriously, how might this change their behaviour and what would be the consequences of this?

So let’s apply these questions to Graham’s statement, or at least the sound bite that people have focused on, ‘that’s not a Bible issue’.

What is he saying? The ‘that’, which Graham considers ‘not a Bible issue’ is the idea of a government policy that would ‘let everyone in who wants to come’. There is no biblical command, says Graham, requiring a country to do this.

A response to Graham’s comment that simply lists the multitude of biblical injunctions to welcome the stranger and care for the alien doesn’t directly address what he is saying. It is not the biblical requirement for caring for the vulnerable he is questioning; it is how that requirement should, or should not be adopted as government policy. The problem is, of course, that Graham has set up a ‘straw man’ by arguing against an extreme idea of uncontrolled, completely free immigration.

How does he know? How does Graham arrive at his view? What assumptions are at play? The logic seems to be this:

- Something counts as a ‘Bible issue’ if there is a specific commandment about it;

- The opposite of the policy is the uncontrolled letting ‘everyone in who wants to come’;

- The Bible does not command a country to do this;

- Therefore this policy is not a ‘Bible issue’ and is allowable

The logic doesn’t work on a couple of fronts. Defining a ‘Bible issue’ this way is a very narrow way of understanding biblical ethics. It is essentially requiring proof-texts for behaviour and policy rather than the construction of biblically informed frameworks with which we can think ethically.

The argument is also advocating against a form of immigration policy that isn’t (to my knowledge) being debated. He is not arguing against a representative view of critics of the policy, but a straw man. In this way the opposing view is dismissed by association with the extreme form.

So what? What’s more important: the way an argument is made, or the effect that it has?

Graham’s statement has been used to give credence to the current government policy. It implies that the policy is not incompatible with biblical teaching and, therefore, provides a biblically satisfying way of supporting the policy.

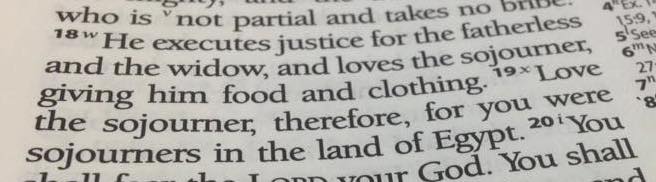

In my view it is a way of deflecting the debate because it has the effect of undercutting the biblical teaching on caring for the vulnerable. It places biblical objections to the policy (i.e., the views of those within the Church opposed to the policy) to the sidelines. It basically says that because the Bible does not have an explicit commandment requiring an extreme form of a specific government policy, the Bible is therefore irrelevant to this matter. Hence, it is not a Bible issue.

I have written previously on the Bible’s call to care for refugees and asylum seekers. In my view Graham’s way of justifying his support for the policy is based on an argument that does not stand up to scrutiny. It seems to me that in this case the Bible has been used inappropriately and unjustifiably, but that it has the effect of giving the perception of biblical credence to the policy, and this needs to be challenged.

As I said at the start, this post does not attempt to tackle all the issues in the debate. I do not believe the Bible can be used legitimately to justify the policy under debate and I am deeply concerned with the way it has been used. The focus of this post has been about the latter.

My main point is this: if we are going to evoke the Bible when discussing controversial issues (whether ‘within the Church’ or in the ‘public sphere’) let’s do so rigorously. And that applies to me too.

If you want to develop rigorous thinking about the Bible, faith and society, why not sign up for a Redcliffe MA programme in Contemporary Missiology? Join with others from around the world at this year’s 3-week MA intensive in July. Find out more