(Originally posted on my substack)

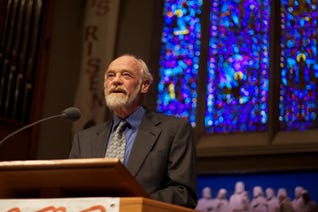

Back in 2006 I was working for St Andrews Bookshop and in the early stages of my Old Testament PhD. One of the most significant writers for me up to that point was Eugene Peterson. His books like Working the Angles and Under the Unpredictable Plant had been transformative, particularly at moments where I was feeling tired and cynical towards ministry.

Every now and then I would do an interview with an author for St Andrews website or magazine and a colleague asked if I wanted to go up to the Christian Booksellers Convention where Peterson was doing the Bible readings. His UK publisher Hodder & Stoughton had brought him over from the States to promote Eat this Book: The Art of Spiritual Reading, the second volume in his Spiritual Theology series.

The following is the transcript of the interview that came out of it. I still have the recording on a micro-cassette (remember those?). Maybe one day I’ll figure out how to digitise it, clean up the background hiss, and post the audio too.

I hope you enjoy reading it. Peterson died in 2018 aged 85. I still go back to his books, and remember that day fondly; it was a warm conversation that feels just as relevant 18 years on.

Tim Davy: Firstly, tell us a bit about yourself and what you are doing in the UK at the moment.

Eugene Peterson: Well, I’m in the UK at the moment at the Christian Booksellers Convention at the invitation of Hodder & Stoughton, who are the publishers of a new series of books I’m writing on spiritual theology. The second one is just published and is called Eat This Book. It’s on the art of reading Scripture, ‘spiritual reading’.

I grew up in a small town in Montana. I grew up in a Pentecostal church and ended up as a Presbyterian. I thought I’d be a professor; I was preparing to be a professor and actually did start out being a professor of Hebrew and Greek in a seminary. But then I had what I call a conversion; it was a vocational conversion. I realised what pastors did and I just thought, ‘That’s what I’ve always wanted to do’. I’d just never realised what was involved, but circumstances converged to put me in a place where I realised, ‘That’s my identity’.

So while I’ve taught a good bit through the years in different places (I ended up for 6 years at Regent College as a professor), I’ve always had this self-identity as a pastor, and in fact I still do: that’s who I am.

TD: Do you think that your pastoral identity was particularly crucial when you were writing The Message, which I suppose you are most well-known for?

EP: Oh yes, definitely. I could never have done The Message without being a Pastor. The Message distils years and years and years of preaching, teaching and praying. But central to all that was attempting to get the message of the Bible, the message written in Hebrew and Greek, translated into the language these people I was working with were living.

So all through The Message pastoral work was kind of the catalyst that formed those phrases, those images, the colloquialisms. And I wasn’t doing it for America or the UK; I was doing it for my congregation. So it was very local; I had three or four hundred people that I was doing that with, although I didn’t know what I was doing at the time. I never had any idea it would become The Message.

TD: Do you see the role of pastor, theologian and biblical interpreter as all being one vocation?

EP: They have been for me. But the catalyst that pulled those things together was the congregation: local, personal, involved with all the mess of community, sin, salvation. For me, I never felt I quit being a theologian when I became a pastor, and I never felt I quit being a biblical exegete when I became a pastor; they were just incorporated into something more personal and local and present.

TD: You mentioned the word, ‘mess’. One of the things I’ve got from your writing is this idea of the pastor recognising God in the mess and how life is untidy and people’s spiritual experiences are untidy. Is that a common view in the world of church leadership?

EP: You know I don’t think so! Many pastors have the self-defined role of ‘tidying up’ the congregation; making it presentable and dressing them up, washing their face, making sure their noses are blown. And of course, in so much of our culture today, churches advertise themselves or present themselves as these glamorous, glorious places where everybody has their problems solved, everybody sings and praises the Lord. I think it’s all a lie; it’s hypocrisy. I’ve never known any congregation like that and I think a good number of people stay away because they are presented like that. Other people join because they think it’s going to be like that but I think the most accurate description of a Christian congregation is the Hebrew phrase tohu v bohu (formless and void – from Genesis 1:2). But what happens in that tohu v bohu is that the Spirit of God moves over the face of the waters and that’s where the creativity takes place. God says, ‘Let there be light’, ‘Let there be Tim’, ‘Let there be salvation’, ‘Let there be this healed body’. But it takes time; I don’t think it happens in six days!

TD: I was flicking through Christ Plays in Ten Thousand Places this morning, where you say that “Sunday is no longer a rehearsal of escape… it is an exposition of the week”. So, that’s the same kind of thing?

EP: Yes, exactly.

TD: I can remember exactly where I was when I read the first two pages of Working the Angles. I know you’re a fan of Dostoevsky; they reminded me of Notes from the Underground in which the first page slaps you in the face and grabs your attention!

You say in Working the Angles that you are an angry pastor; that you felt abandoned. Are you still angry?

EP: I don’t think I’m still angry but I still get angry. I don’t think anger is a prominent part of my life, but I do get angry, Tim. I get angry that so many pastors and leaders take this with so little seriousness. I mean, we’re dealing with really important things and they play games, they devise silly programmes, they fool around trying to find a way to get more people into their church.

I don’t know what it’s like here but in America there is a huge trivialisation of the Church, and that makes me angry. When you see what is precious and valuable and eternal being treated like a piece of commerce it makes you angry.

But for me the anger is momentary and it ignites something (usually a book!) and I work it out, trying to go back again and start at the beginning, and work out all the implications of this. I try to show people how everything is interrelated in this; it’s all interrelated by the Spirit of God – the operations of the Trinity.

But I think anger is a good triggering emotion for me; it doesn’t sustain me but it pulls the trigger. Richard Hugo, a good poet from Montana, has a poem called The Triggering Town. It’s about towns he goes through and something in that town triggers something – an image, a metaphor – and then he writes this poem. There’s always a triggering thing that gets the poem going. Well, that’s true for me with books, sermons, lectures. If there was no mess, I wouldn’t have anything to do!

TD: This new series, Spiritual Theology; is this your magnum opus? Is this what you’ve been building up to say over your ministry?

EP: Well, magnum opus seems a little bit pretentious, but yes it does feel that way. I feel like I’m getting everything together that I’ve been doing all my life and I hope I can fit it together well.

In some ways, when I did The Message, I had the feeling that it was a kind of a culmination of things. This is my whole pastoral life redrawn into the Scriptures and expressed in a way that was part of my congregation.

If I had to visualise these five volumes of Spiritual Theology, this is the underground of The Message, the background. This is all the thinking and the exegesis and observation that produced The Message.

TD: So, ‘the man behind the message’?

EP: Right.

TD: Your new book, Eat This Book, is about ‘spiritual reading’. What precisely do you mean by spiritual reading?

EP: It’s a way of reading. It isn’t confined to Scripture; it’s a way of reading anything. I guess I would contrast it with informational reading (like when you read a mathematical textbook or a history book – you’re trying to get the facts), or functional reading (reading to know how to do something, like a manual for reworking your carburettor). And then there’s another kind of reading I guess I would call inspirational reading, where you read to feel better, to clarify your thoughts. And of course there are other kinds of reading, like entertainment, mystery stories.

But there is a reading in which you let the author, let the book change you. Now, this is not my stuff, this is not new; it’s ancient. You are not going to the book to get something that you want; you are going to receive something that the writer wants to do. Revelation is what it is. It can be in a poem – we read most poetry this way: not to get a meaning but to let it shape a way of insight in us. We are not in control; that’s the key thing. We’re letting the author be in control. So we don’t keep asking questions like, ‘What does this mean?’ or ‘How did he get that?’. We are submitting to the mind of the maker (to use Dorothy Sayers’ phrase) and letting something be made in us. So this is what spiritual reading has always been.

The interesting thing (and in some ways the disconcerting thing) is that for a thousand years at least this was the major work of the Church. This is what pastors did. This is what theologians did. They taught people how to read receptively, rather than as a consumer. And then with the rise of the universities in the 12th century things shifted and we looked at a book now as something to be mastered or gotten something out of or explained. And this predominant way of reading, that was developed for a thousand years at least, kind of got pushed to the periphery. Monks did that; pious people did that. But if you’re really on the cutting edge of things you figure it out, explain it, use it.

TD: It reminds me of my own field of Old Testament Studies, with the changes in the last few decades with canonical criticism, ‘confessional readings’ as some would put it, accepting the final form of the text rather than dissecting and atomising it, which I think you touch on in another book.

EP: In Working the Angles I do that. I’m not sure I use the term ‘canonical’ but Brevard Childs influenced me a lot. William Albright was my professor.

It’s interesting to me, and maybe this is just a prejudice and probably wouldn’t hold up to any examination, but Old Testament scholars have been the pioneers in this, for me. They are the ones who discovered Scripture as narrative. They got fed up with this whole source criticism as a way to approach Scripture, and began discovering the world in which it was done, rather than trying to sort out the fragments and take them apart and show them.

TD: Is that because there is more about creation in the Old Testament, or is the Old Testament messier?

EP: I think it’s messier.

TD: I think that’s why I like it!

EP: Me too! Yeah, it’s messier; it’s just not the sum of its parts. It’s like somebody took apart an engine and started to put it back together again and then they have these parts around that don’t fit. But they do fit. Yeah, I like the mess too…

Are you reading anything in particular over the Lent period? I’ve chosen a couple of things to work through between now and Easter. The first is a new book by Lynn Japinga on

Are you reading anything in particular over the Lent period? I’ve chosen a couple of things to work through between now and Easter. The first is a new book by Lynn Japinga on